Gavi is one of the most famous white wines of Italy, especially for the UK. The region exports 85% of its wines and nearly half of those exports end up on our shelves or wine lists. Does everyone know the grape variety? Probably very few. Does everyone know it’s from Piemonte? Again, not likely. I’d wager a fair few wouldn’t know it’s Italian, but the name of ‘Gavi’ has reached a level of recognition in the UK that few regions could hope for.

Described by one UK wine writer recently as: “Pinot Grigio for posh people” (make of that what you will), these soft, fresh, floral, and fruity wines are simply so easy to enjoy. Whether served amongst friends with the perfect food pairings, or (sadly) ice cold after three days in a fridge to celebrate making it to Wednesday, a glass of Gavi is an affordable luxury for most households.

As with so much in life, however, the way we think and talk about Gavi as a region, or a set of wines, is all too simplistic. On a recent trip to the region, I was lucky enough to tour the terroirs, experience the unique culture, take in the rich history, and try some wines that have forever altered my perception of this beautiful part of North-West Italy.

Where is Gavi?

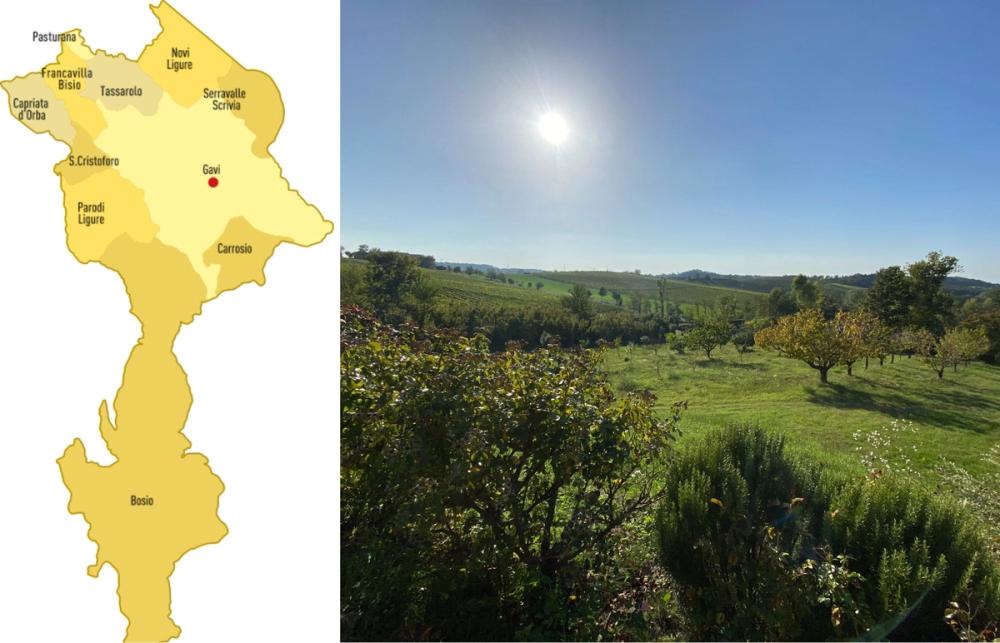

X marks the spot...

Gavi is the name given to the wine region based around the fortress town of the same name. It’s based in the Alessandria province of Piemonte in North-West Italy with vineyards stretching 30kms north to south, and 15km west to east at its widest point in the north.

The landscape is quite confusing. Usually if you stand in a mountainous area and look towards the sea, you’d expect the land to gently slope down to the coast. In Gavi, it’s the opposite. The way the land has formed over millions of years saw the Piemontese Apennines rise, cutting off an inland sea from the rest of the Mediterranean. The Apennines are still there, forming a very present, physical barrier between the wine region and the sea just 30km to the south.

Gavi sits on a hugely important historical trade route from goods going in and out of the thriving port of Genoa. Wine was first recorded in the area as making wines for the court of Genoa back in 972AD, and the region was a haven for the homes of the great and the good of the Genoese court as part of Liguria. In 1815, the House of Savoy was granted the region as part of the Treaty of Vienna and became part of today’s Piemonte. Its Ligurian roots have not been forgotten and the Ligurian-Piemontese cultural mash-up makes it a truly unique part of Italy that can be enjoyed at producers such as Villa Sparina, Wine Enthusiast’s Best Winery in Europe in 2021, with impressive focus on wine tourism reflective of the region as a whole.

The Comunes of Gavi

Comunes of Gavi and the slopes around La Raia

The famous wines of Barolo and Barbaresco have, in recent years, famously launched their terroir specific UGAs. The unità geografiche aggiuntive translate as additional geographical units. It’s simply codifying the differences in terroir across the wine regions that many people have known for years. Big issue is the number of them. If you include the separate communes then Barbaresco has 66 and Barolo has 181!

Mercifully for Gavi there are only 11. Well, 11 comunes at least. The map above will show you where they all are. You have Gavi itself in the middle, but otherwise? Are you expected to know the other 10 if you’ve not been there? I’d say it’s more of a 'not yet', rather than a hard 'no'.

It has been argued in the past that the Cortese grape may not be the best to show off the differences in terroir, or that the styles from each UGA are not consistent enough just yet.

What is clear, however, is that in the discussions I heard on my trip producers are increasingly referring to the different UGAs in blending discussions and the regional grape market come harvest time.

Andrea Pancotti is the director and winemaker at Produttori del Gavi, the regional co-op started in 1951 managing the vineyards of 80 families across the region.

“We like to keep the grapes separate so we can make the offering to customers,” says Pancotti. “Fruit from Capriata D’Orba’s red soils goes into the fuller style of our G label, with fruit from Gavi’s white soils goes into our GG label. In 2023, the market paid about 20% more for Gavi commune fruit, but that can change on vintage.”

Frazionis

Mike Turner had the chance to taste wines from across Gavi during his recent trip

In addition to the 11 communes are seven smaller designated frazioni with two each in the communes of Bosio and Parodi Ligure, and three in the commune of Gavi. These are specific areas within a commune where soils or topography change enough to make them worth standing out.

The three in Gavi - Monterotondo, Pratolungo, and Rovereto – are the only ones I’ve seen on labels so far. But it’s clear there’s a quality distinction made by wine producers.

Gianlorenzo Picollo runs Picollo Ernesto in Rovereto whose clay soils demand a premium. “The great thing about Rovereto is the great exposure we get,” explains Picollo. “The vineyards are about 50% more expensive than elsewhere, but the wines are more floral, concentrated and coating.”

Labelling remains a challenge. The unregulated marketing attempt to use ‘Gavi di Gavi’ as a form of quality marker has left many unhappy.

“Gavi di Gavi is confusing and shouldn’t be used anymore,” says the Consorzio Tutela Del Gavi's chief agronomist Davide Ferrarese.

“People who still use it are just being lazy as it’s quicker than the proper name.”

Those with vines in the Tramontana frazione, in the commune of Parodi Ligure, have three labelling choices; as Gavi, Gavi del Commune di Parodi Ligure, or Gavi del Commune di Parodi Ligure Tramontana. As much as I agree with Ferrarese, you can see why people take the short cut.

Climate and soils

Terre Bianche, Terre Rosse and Andrea and Nora Spinola

Gavi has a cool continental climate that is dominated by winds. The vineyards of Marchese Luca Spinola cover areas in both Tassarolo and Gavi, with current owner Andrea Spinola the first of the family to establish a winery and bottle under their own name.

A terrace tasting of their range was a perfect way to experience the winds. “We have the Col Marino, a moist, southerly wind which gives us amazing freshness,” says Spinola, masterfully controlled his flowing locks. “We also get a northerly, drying wind too, so there aren’t many days of calm in the vineyards.

Much of the rain is also stopped by the surrounding mountains, allowing many (including Spinola) to certify in organics or biodynamics.

Paola Rosina, co-owner of La Mesma in Gavi’s Monterotondo, remembers their own journey: “We started with organics on just one rented plot,” says revealed the Genovese native. “We were starting from very little, so we needed to know it would be economically viable.”

By 2017 the full 10 hectares of vines were certified organic, with biodynamic methods cherry picked for their efficacy.

“We love trying what we can to naturally improve our vines and soils.”

There are two main soil types that define Gavi. Firstly, the Terre Bianche (white soils) covers the land that used to be underneath the inland sea. It has limestone-based clay soils with alternating marl and sandstone. The limestone gives a more alkaline soil type meaning the wines from this central strip of the region tend to be slightly lower in alcohol, more perfumed and fresher. They dominate the communes of the likes of Gavi, San Cristoforo and Bosio.

To the north is the Terre Rosse (red soils). These are iron-rich mixes of gravel and clay formed by the alluvial deposits of inland rivers. There is much less limestone around here, meaning slightly acidic soils and fuller, more structured wines. These red soils dominate the communes of the likes of Tassarolo, Capriata D’Orba and Novi Ligure

Synonymous with Cortese

Cortese grapes and Davide Ferrarese hugging one of his data capture stations

Gavi is Cortese and Cortese is Gavi. On the inception of Gavi DOC in 1974, the wines allowed only 100% Cortese, a rule reiterated in the documents for the elevation to DOCG in 1998. There are 1600 hectares of Cortese now planted in Gavi, which represents 60% of all planted Cortese in Italy.

The Consorzio Tutela Del Gavi has worked hard since its inception in 1993 to promote the best that Cortese can offer. Thorough ampelographical studies have been undertaken to ensure the Gavi vineyards are 100% Cortese. Since 1997 it has worked closely with the National Research Centre in Torino to aim for the best clonal selections for each vineyard and the oncoming challenges of climate change.

“We’re studying the climatic differences year on year,” says Ferrarese as he proudly displayed one of the Consorzio’s weather stations at Marchese Luca Spinosa. “It’s all about being able to adapt our approaches as quickly as possible for the vintages to come.”

Cortese and Gavi are particularly well suited to cope with the immediate threat of climate change. It’s high acidity and medium bodied nature means it continues to offer freshness even in warmer years, arguably adding an intensity of those citrus, green fruit and floral notes that can been lacking in cooler years.

Styles and ageability

Metodo Classico Gavi

The vast majority (99%) of Gavi produced is in the classic still, white wine category. Within that 1%, however, are some very interesting wines. We tasted more than our fair share of sparkling wines, mostly made in the Metodo Classico style.

It makes sense. Cortese is high acid grape variety that will enjoy the extra autolytic character. The rules only demand nine months of lees-ageing in bottle, but most I tried were longer and in the brut style.

The Metodo Classicos made by Francesca at Il Poggio di Gavi in Rovereto certainly hit the mark. “The freshness of Cortese makes it a clever grape,” says Poggio. “That’s why our Metodo Classico is called L’Ape, it means 'the bee' and bees are clever. It’s also short for Apéro, so maybe we think we’re clever too.”

A new, but little used category is Gavi Riserva DOCG. Introduced in 2010, the wine must but aged for at least one year after harvest, with at least six months of that in bottle before release.

Slightly lower yields, slightly higher minimum abv. The usual. The big issue, though, is that you must declare which vineyard you’re going to use for Riserva wines before the vintage starts. It gives winemakers very little flexibility to deal with the ups and downs of the year in the vineyard. Most have simply decided to ignore it.

“It’s a strange one,” says Clara Milani, oenologist at the biodynamic La Raia in Novi Ligure. “We were one of the first to use it because we wanted to signify that Gavi could be age-worthy, but I understand why many choose not to.”

The age worthiness of the wines of Gavi was one of the more interesting aspects of the trip as we sampled aged versions of some of the cru-level wines. The minerality, balance and flavour concentration were there to allow these wines to age for up to a decade, developing honeyed, nutty and sometimes petrol notes.

“A few years ago, we did a tasting comparison with new and aged Gavi against new and aged Chablis,” remembers Ferrarese. “The comparisons were stark and gave us real hope that we were on to something with high quality, age worthy Gavi.”

For more information about the wines of Gavi or the work undertaken by the Consorzio Tutela Del Gavi, please contact Irene Ferri at Wellcom on irene@wellcomonline.com.

You can read a report on The Buyer's recent Restaurant Tour with Gavi wines with buyers, importers and wine writers in and around Manchester by clicking here.

Mike Turner is a freelance writer, presenter, educator, judge and regular contributor for The Buyer.

For those of you looking to sample the wines of the producers mentioned in the above article, here is a list of their current UK importers:

Villa Sparina: FortyFive10: https://www.fortyfive10.com/

La Raia: Passione Vino: https://passionevino.co.uk/

Il Poggio di Gavi: Amathus: https://www.amathusdrinks.com/

La Mesma: Raeburn Fine Wines: https://www.raeburnfinewines.com/

Picollo Ernesto: Passione Vinohttps://passionevino.co.uk/

Marchese Luca Spinola: Gardabani Wines https://www.gardabaniwines.co.uk/

Tenuta San Lorenzo: Champagne & Châteaux https://champagnesandchateaux.co.uk/

Produttori Del Gavi: Alliance Wine https://www.alliancewine.com/