Ahead of the publication of his second wine book – which is a deep dive into the world of Portuguese wine – Simon Woolf looks into the disruptive world of wine book publishing.

When Decanter contributing editor and Rhone wine expert Matt Walls tried to get an agent to look at his first wine book in 2011, he was politely told: “If you don’t have a TV show or a column in a national newspaper then forget it.”

It is every writer’s dream – the phone call from a major publishing house, with a commission to write The Book that will cement their reputation as the world’s leading expert on [insert micro-niche here]. And the subsequent fame and fortune that will naturally follow the book’s publication.

For most who write about wine, this scenario remains just that – a dream. The traditional publishing world has cut its lists for serious wine non-fiction to the bone – witness the 2002 sale of Faber & Faber’s once legendary wine list to Mitchell Beazley, who then put most of it unceremoniously out to grass.

Walls managed to get his book in print though – as he says, with a healthy dose of luck. He was recommended to Quadrille publishing, who had just launched their “New voices” series for unpublished authors. And they were looking for a wine title.

Matt Walls was able to break into wine writing on the back of the success of his first wine book – Drink Me

The book, “Drink Me”, sold 10,000 copies and helped launch Walls’ career, enabling him to give up his day job in retail and become a freelance wine writer. It also put a decent chunk of money in his pocket. But this kind of publishing success is rare in wine.

Lost in a forest

Nonetheless, every year a forest of new wine books hits the shelves, ranging from the utterly predictable (yet another book about Champagne, yet another book about rosé) to the fantastically niche (in 2020 for example, a catalogue of Swiss native grape varieties and a 160 page tome on the relationship between wine and God).

How does this work if wine publishing is supposedly on its knees? Many of these books didn’t go via a traditional publishing house. Just a few decades ago, publishers were the only route to market. Now, a book might be self-published, print-on-demand (POD), short-run, digital only, crowdfunded or various hybrids mixing all of the above. But which of these models work well for wine, and which serve the author or the reader best?

Self-publishing used to be regarded as little more than vanity publishing, for those were willing to pay handsomely to have their name on the spine of a book, but whose work would never trouble the book-buying public. It has evolved rapidly over the last decade, and now encompasses everything from cheap print-on-demand paperbacks (of the sort published and sold directly by Amazon) to professional affairs which are indistinguishable from the output of a top publishing house.

Jamie Goode has used his wine books as a vehicle to be seen as an expert in key areas of wine, which have then helped him gain paid for speaking opportunities at major events

Jamie Goode, one of the UK’s most prominent wine writers and author of five non-fiction books, recalls that in 2004 when he was pitching his first book “self-publishing was treated with a fair bit of suspicion” whereas now by comparison “there is absolutely no stigma attached to it at all”.

All of Goode’s wine non-fiction to date has been published by University of California Press (he’s one of a select group of authors left on their wine list), and many of his books are standard issue for wine students. Yet Goode admits that none have been big earners – not even his best seller “The Science of Wine”. Goode received advances for everything apart from his book about wine faults (“Flawless”), which even UCP felt was “too niche” to be a sure sell. His royalty deal is 10% on net sales, which could mean as little as 60p per copy sold on a book with a cover price of £20.

Jam today or jam tomorrow?

Let’s take a look at what these terms actually mean. Advances are a key construct in traditional publishing. The author receives a lump sum a year or more before publication, which theoretically funds their time spent researching, writing and delivering the manuscript. Advances are non-refundable, meaning the publisher takes a gamble that the book will actually sell. Thus the size of the advance is usually linked to the revenue the book is expected to generate.

The author must then ‘earn out’ the advance before they receive any further payments, in the form of royalties. Royalties are often the subject of intense contract negotiation, but are typically between 8% to 12% per copy sold. If this percentage is based on the cover price of the book, the author can earn a reasonable cut. However, authors are increasingly offered a net royalty in some or all cases – a percentage not of the cover price, but of the selling price.

The publishing sector is dominated by whatever Amazon does next

If the publisher sells the book direct to a customer at the cover price, there’s jam all round. But sales to a retailer are typically at a 40% discount, and to a wholesaler or distributor can be at as much as a 70% discount. Amazon, like it or not a key driver for the success of any book, demands a 55% discount from its suppliers – 10% of 55% is a very different prospect to 10% of 100%

Goode acknowledges he might have made more money had he self-published. He is now considering this route for his next book. But he also notes that even if his books only delivered modest financial benefits to date, they’ve been hugely important to his career “in terms of building reputation and unlocking the US market”.

Publishers are well aware of the ability for an authoritative non-fiction book to transform its author’s profile. This is the justification for why their financial models often seem skewed to put the profit in the publisher’s pocket, leaving only the glory for the author.

Infinity and beyond

Since the demise of serious wine lists such as Mitchell Beazley, a small UK publishing house stepped into the fray in 2012. Infinite Ideas originally established itself in 2003 as a publisher of self-help books, and then moved into business books. As director Richard Burton explains, their wine list (The Classic Wine Library) came about after they published two independently sponsored books by Richard Mayson and Julian Jeffs. “We realised they were doing quite well outside the subsidy, so we appointed some serious editors and decided to do it properly,” he says.

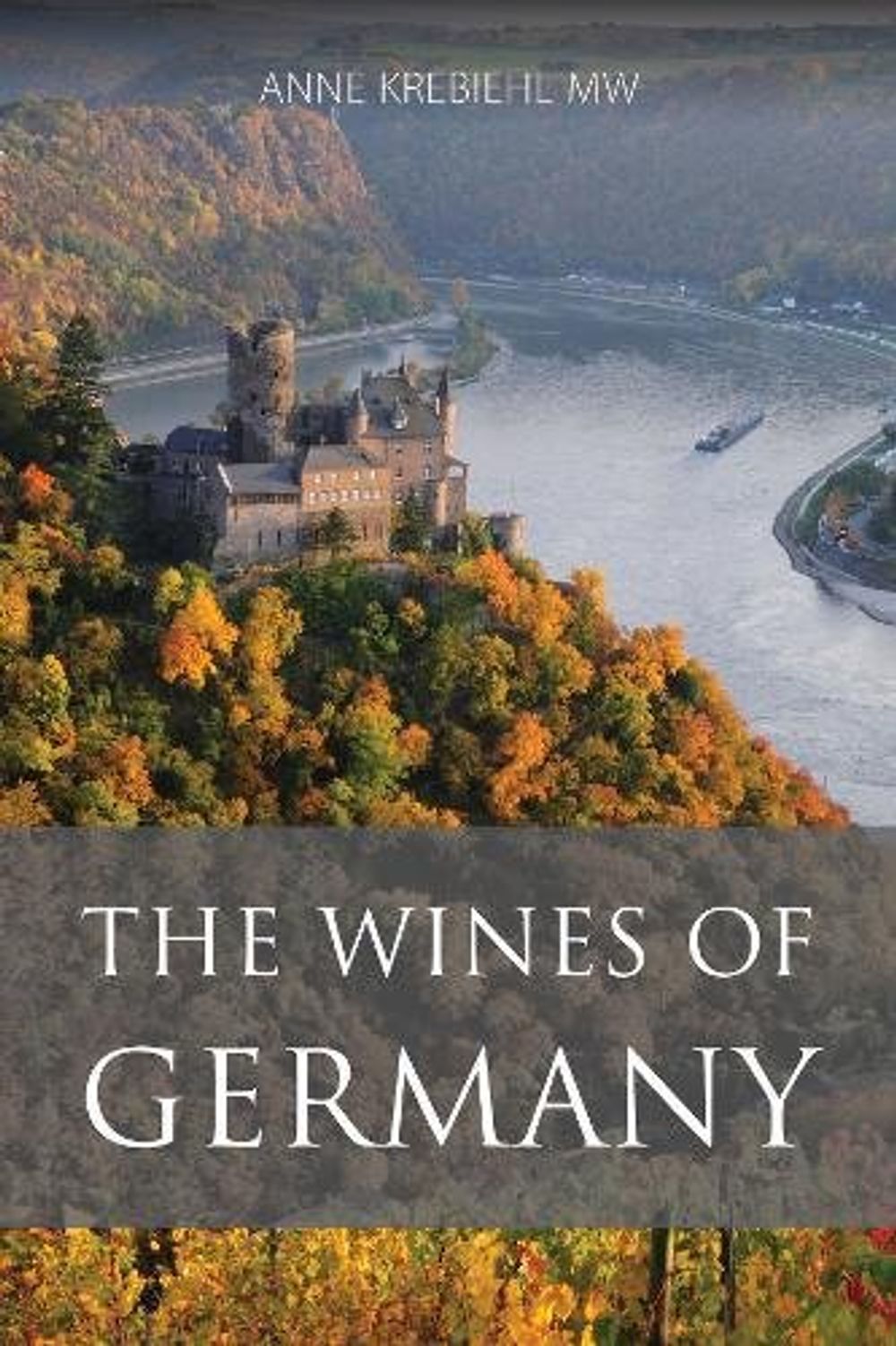

Anne Krebiehl’s book The Wines of Germany won International Wine Book of The Year” award at the Louis Roederer Wine Writers’ Award 2020

The Classic Wine Library has swiftly expanded its list to 29 titles, authored by an impressive cast of leading experts and Masters of Wine. German-born, UK resident Anne Krebiehl MW is renowned for her writing and consultancy on German and Austrian wine. She was called by Infinite Ideas in 2017, with a commission to write a book about the wines of Germany. “I was immensely flattered” she says. “This is what every writer wants to happen, that someone approaches you because you are the voice of a country”.

Krebiehl had misgivings over the dated look and feel of the books, and the contract, but decided to proceed “with eyes open”. By the time her book was published in 2019, her initial enthusiasm had more than evaporated. Infinite Ideas pays no advance to its authors, effectively requiring them to self-fund their research and writing time. Once the books are published, the authors then wait for a year before they receive a royalty statement and the promise of eventual payment.

Infinite’s royalty model is net rather than gross, and Krebiehl estimates that she receives around £1.76 per book sold. Burton talks of her book (which won the Louis Roederer Wine Awards Book of the Year in 2020) as one of the list’s top sellers. No-one talks in exact numbers, but reading in-between the lines suggests that this means between 2,500 – 3,000 copies sold in the 18 months since the book’s publication.

Krebiehl says the research required two years of effort. Only basic arithmetic is required to see that unless an author is independently wealthy, or able to leverage a vast amount of support from the relevant generic body (Krebiehl had basic travel costs funded by The German Wine Institute), there is no financial worth in delivering a book under these conditions.

Krebiehl’s dissatisfaction with Infinite Ideas extends to what she sees as a lack of proactiveness when it comes to promotion. Her feelings are echoed by many other authors in the series, amongst them Elisabeth Gabay MW and others who did not wish to be named.

Matt Walls has just published his latest book “Wines of the Rhône” with Infinite Ideas. He agrees that “the deal isn’t brilliant” but says that he felt his book had to be written – and that it’s “fairly normal for an academic book”.

Burton is adamant that he tells authors upfront not to expect to get rich off the royalties: “Their money comes from elsewhere,” he says, “from higher speaking fees, more tastings and better profile in the industry”.

Does he feel that this stripped down model is sustainable? He responds matter-of-factly: “We’re a business and it’s important for us to make some money. Otherwise we’ll just stop – and we have thought about stopping.”

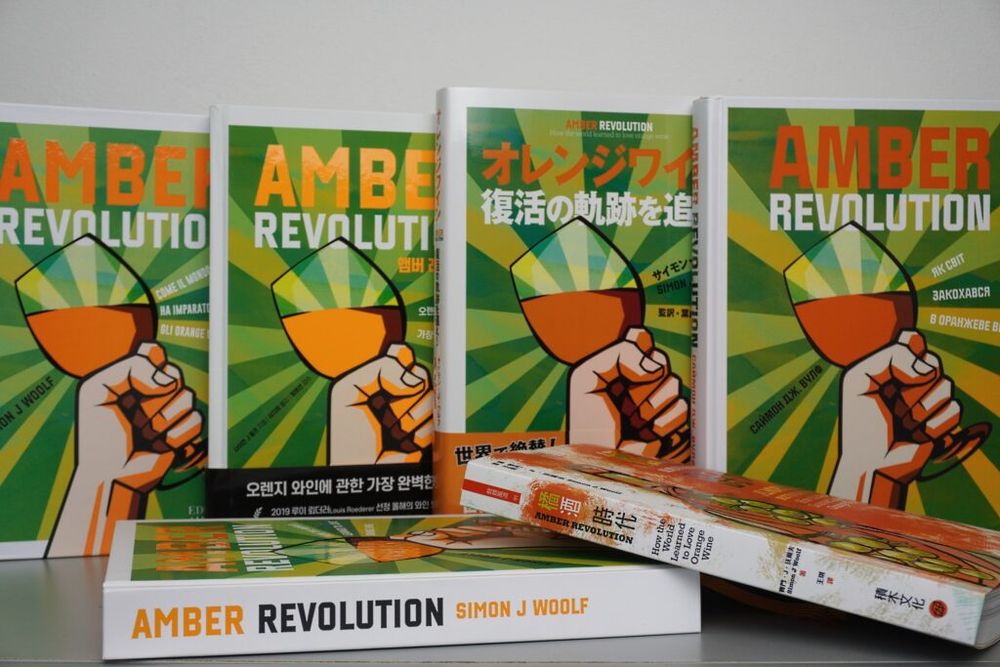

Simon Woolf’s breakthrough debut book on orange wines

As Jamie Goode implies, one reason that authors choose to self-publish is to retain more profit for themselves, rather than settling for the penury of a poor royalties deal. My experience with my first book “Amber Revolution – How the world learned to love orange wine” in 2018 demonstrated that self-publishing can deliver substantial financial benefits. But it’s a model that requires considerable organisational and self-promotional effort.

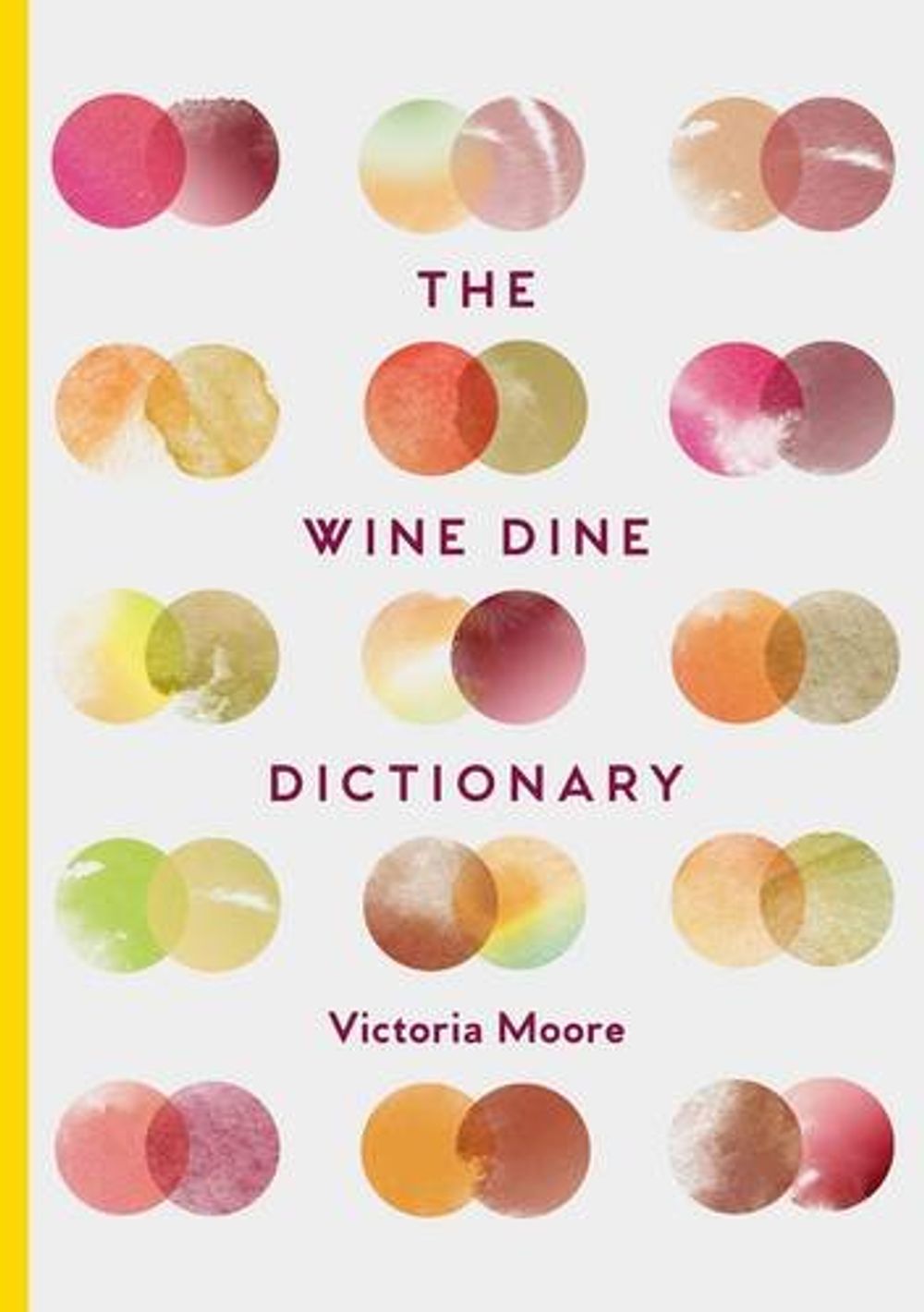

Everyone who has worked with a major publisher understands the value of having a large team work on a book. Victoria Moore is wine correspondent for the Telegraph and author of the best-selling “Wine Dine Dictionary” (Granta, 2017). Moore became a mother, and a single parent, while working on “Wine Dine” and says: “I can see huge attractions in the self-published model, but it would not have worked for me at that point in my life”.

Victoria Moore’s Wine Dine Dictionary had the power of Granta behind it

She recalls that it was a hugely fulfilling experience to have editors, designers and indexers work on bringing her book to life. Proving the rule that having a column in a national newspaper puts you in a different league, Moore and her agent were able to secure a major advance for the book. Its crossover into food also no doubt helped unlock a bigger market.

Going it alone

With self-publishing, the author must manage all aspects of the book’s production alone – starting with sourcing the funding. I took on this challenge in 2017, after my book was rejected by 13 publishers worldwide. It wasn’t a surprise that no-one wanted to take a risk on an unknown author, and a ridiculously niche subject (orange wine).

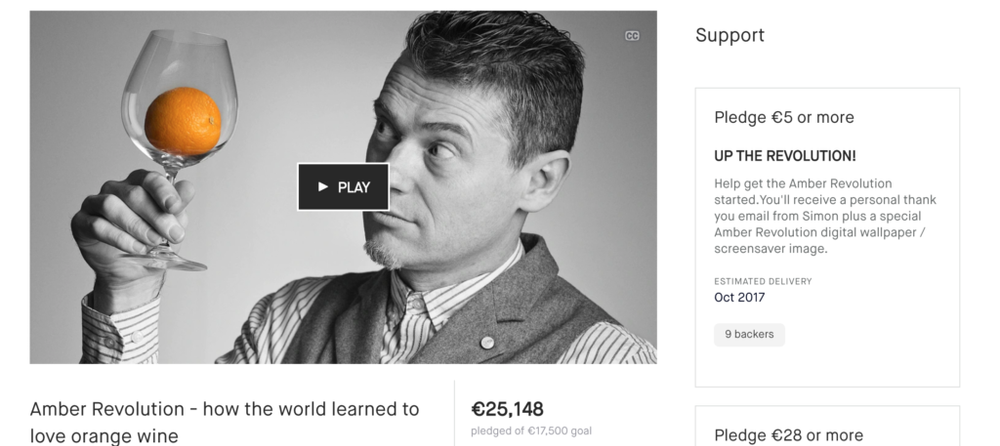

Here’s a screengrab from Simon Woolf’s Kickstarter page to help fund his Amber Revolution book

I crowd-funded on the Kickstarter platform, raising €25,500 which was just about enough to cover the costs of production: design, photography, a copy editor and the printing itself. This was without doubt the most nerve-racking part of the whole exercise. I didn’t have a column in a national newspaper, but I did have a reasonably active following on social media, which was essential.

Kickstarter is vital because it demonstrates whether or not a project has legs. When a campaign fails, the chances are it wasn’t ready for prime-time or didn’t have an audience. Kickstarter shouldn’t be seen primarily as a way to raise money. Its real value is to create buzz and to drive pre-sales. By the time Amber Revolution hit the printing presses in June 2018, I had pre-sold over 900 copies and effectively broken even. It should have been cause for celebration, but when the books arrived in Amsterdam the grim reality hit: the person who was going to package up all those books and take them to the post office was me.

Conquering the world

Foreign rights – where a publisher buys the rights to publish your book in another language – are an additional source of income, but publishers typically take a 40-50% cut. Amber Revolution has been translated into five foreign languages, and I negotiated four of those deals myself. So I got all of the money. It didn’t quite secure the super-yacht, but did equate to a few months’ income.

I’m not going to flirt, here are the figures. Amber Revolution has to date sold almost 7,000 copies in the original hardback edition, plus at least another 4,000 in five foreign language versions (not all of my overseas publishers send timely royalty statements). A third printing and a paperback edition arein the pipeline later this year. The vast majority of these sales only happened thanks to proper distribution. I was extremely lucky that a chance recommendation secured me a US and UK distributor in one go.

Sharp-eyed readers will notice that the front page of Amber Revolution mentions a US publisher, Interlink Books. Interlink usually publishes its own titles, but came onboard at a late stage with Amber Revolution purely for promotion and distribution.

This is where the lines between self-publishing and traditional publishing blur. Carla Capalbo is an established and multi-award winning author of wine, food and travel books. She has published her last five books using a hybrid model. Her publisher is Pallas Athene in the UK, and Interlink Books in the US. But although these houses provide the all important distribution and promotion, Capalbo self-funds her books and retains complete creative control over the process.

Carla Capalbo uses a hybrid model to publish the books she wants – so self publishes but works with publishers for distribution

She explains “It gives me the freedom to write the kinds of books I want, and without the constraints of style, content, length or art direction that a ‘normal’ publisher would have to impose to make the accounts work out”. Capalbo learnt an important lesson early on in her publishing career, and says “I will never again give away my copyright, and most publishers nowadays demand that, even the big and famous”. Her most recent book “Tasting Georgia” has been a huge crossover success, due to its mix of wine, recipes and stunning photography.

The only way is us

Many authors of niche non-fiction have found that self-publishing or self-funding is the only viable route to market. Many lauded wine books would not otherwise have seen the light of day. Charles Metcalfe & Kathryn McWhirter’s “The Wine & Food Lover’s Guide to Portugal” (2007) was a front runner, as was Neal Martin’s multi-award winning “Pomerol” (2013). Wink Lorch’s “Jura Wine” (2014) and “Wines of the French Alps” (2019) were both financed via Kickstarter and have become go-to references for their regions.

Jane Anson linked up with Berry Brothers & Rudd Press to help publish her award winning Inside Bordeaux book published last year

One of 2020’s most eagerly awaited releases – Inside Bordeaux by Jane Anson – also took a non-standard route to publication. Anson, one of the world’s leading experts on Bordeaux, explains: “I was in talks with a traditional wine book publisher for a Bordeaux book, then met Chris Foulkes and Carrie Segrave, the publishers of Berry Brothers & Rudd Press, and it became clear that their ambition for the book was not something to turn down”. BBR Press allowed Anson three years to research and write the book and came up with a sufficiently large advance to allow her to do so.

Foulkes and Segrave come from a traditional publishing background, but BBR Press operates on anything but traditional lines. It has only published three books (including Anson’s) since 2010, and focuses on direct sales and distribution throughout the wine industry. Its books are premium priced and not available on Amazon. The model clearly works for major summations such as Anson’s book, and Jasper Morris’s “Inside Burgundy” (which preceded it).

Anson has authored five wine books “without an agent, only two of them via the same publisher and with different routes to market each time”. A collaboration with photographer Andy Katz, “The Club of Nine”, was self-published in 2016. She says: “I would do it again if I could work out how to properly ensure distribution.”

Anson is upbeat about wine book publishing in general: “This past year has shown us that there is still a hunger for stories and connections,” she says “and I am just as in love with books and all that they represent as I ever was, so I feel optimistic about the future.” She does, however, caution that “we need to be disruptors and to find our own ways to connect to readers”.

What’s up next

Ryan Opaz, digital consultant and photographer is working with Simon Woolf on a joint book project to promote Portuguese wine

My own experience has taught me that maybe the glory of being with a traditional publisher is overrated – however much I wanted that dream back in 2017. Amber Revolution has been treated with nothing but respect by the wine world, winning a Roederer award in 2019 and making the New York Times list of best wine books in 2018.

I’m now working on a new book in collaboration with Ryan Opaz (who was the photographer for Amber Revolution). Together, we have conceived “Foot Trodden – Portugal and the wines that time forgot” as a narrative and visual deep-dive into Portuguese culture and wine.

We were delighted with how Amber Revolution worked out, so we’ll be following the same model for Foot Trodden. If you believe in quality wine books, I sincerely hope you’ll support our Kickstarter campaign that is now live.

- If you would like to keep up to date with Simon Woolf and Ryan Opaz’s plans for Foot Trodden you can sign up to its website here. You can also donate and take part in its Kickstarter campaign here.