The wine industry has a discounting problem.

In this photo, taken in Sainsbury’s, 35 of the 86 wines are on special offer - 40% of them. That’s before you take into account the overarching special offer to get money off anything when you buy six or more.

It's nearly harder to find a wine that is not on discount at times in Sainsbury's, says Tom Planer

Take a look in some of the other aisles and it’s a different story - coffee beans? Twenty one perc cent on offer. Cereal? Twenty four per cent. Neither with an overarching offer. Over in Waitrose it’s a similar story. Forty one per cent of wines were on offer, nearly double that of any other category.

You don’t even need to set foot in a Majestic to realise special offers are the main hook. The outside of the store is plastered with offers and freebies, with no mention of their expert staff, or anything about the wines themselves.

According to Mintel, 40% of buyers list special offers as their primary reason for buying a new wine, with only 27% saying recommendations. Did the discounts come first or the customer expectation for them?

Why is wine so hooked on this?

The main reason is that most wine drinkers (about 80%) have no idea what they like.

They don’t know what a Rioja is going to taste like before they open it. They don’t know what tannins are. They don’t really know what dry means. To most, wine is a total mystery.

But people don’t like mysteries, especially when they’re shopping. So they look for something they do know about, to make them feel safe. Everyone knows about money - so shoppers can use value as a proxy for quality.

“It was x. Now it’s y.” “That’s a bargain. I like bargains. I’ll get that one.”

But while discounting might solve the immediate problem of making a sale, it doesn’t solve the real problem of getting customers wines they like. Just because it’s cheap - it doesn’t mean people will like it, and if they don’t like it they won’t come back.

How did we get here?

Majestic's whole retail premise is based on paying less if you six bottles and is constantly sending out online offers

Discounting became prolific in wine in the 1990s as supermarkets started to take a bigger share of alcohol sales from specialists. Their size meant they could get huge volume discounts, which they could pass onto the customer. Because they sold more than just alcohol - they could afford to sell low, because shoppers bought other items at full price while picking up their cheap wine.

Andrew Howard, who worked as a buyer at Marks & Spencer during the period, suggests that discounting really gathered pace in the mid 90s. The 80s and early 90s had seen a buzz around wine, with shows on BBC2 and Channel 4 from Jancis Robinson MW attracting viewers in the millions, wine bars were opening across the country offering an alternative to pubs, non-European wines were exciting and new.

Wine enthusiasm was on the rise, but once retailers had captured the enthusiast market, ongoing growth needed to come from elsewhere. Discounts fuelled this continued growth, but took everyone else in at the same time.

High street specialist chains, who until then had focused on expertise and quality of offering, suddenly felt the need to compete with supermarkets on price and discount too.

Henry Jeffreys, who worked at Oddbins around this time, remembers the first January sales. Whisky and Champagne had previously been discounted, as were large volumes (e.g 6 cases or more), but discounts on smaller volumes of still wine didn’t start to come in until the mid to late 90s.

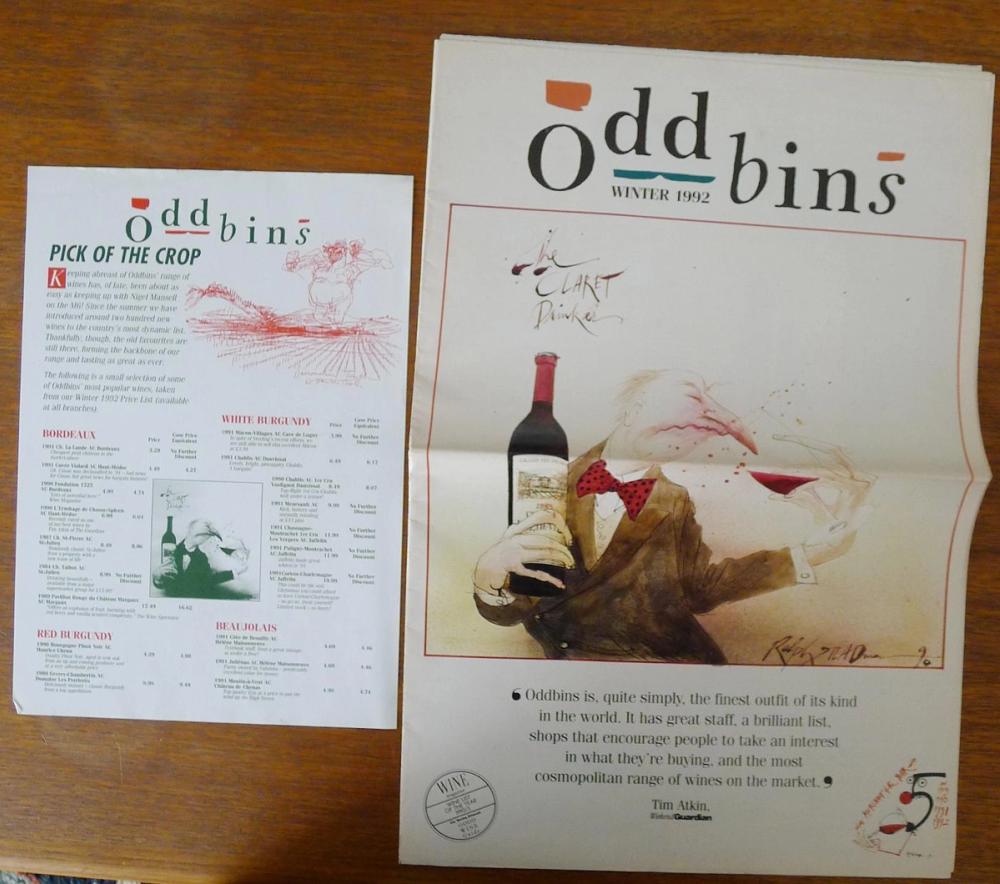

How Oddbins used to promote itself back in 1992

Oddbins comms pre-1995 were mainly focused around quality, product, and brand - with distinctive illustrations courtesy of artists like Ralph Stedman (of Fear & Loathing fame).

Around the mid 90s, special offers started to creep in, but by the 1997/1998 issues of their in-store magazine - discounts & special offers were suddenly front page news.

Around a similar time, First Quench (Thresher’s, Victoria Wine) introduced a 3 for 2 offer, essentially a 33% discount for anyone buying more than one bottle. In an industry where a gross margin might be 30 - 40%, this can clearly only go on for so long, and it did...

Discounting became the main draw, and specialist knowledge declined so much that by 2005, Wine Rack (Thresher’s) saw fit to employ yours truly, who knew the difference between red and white, and not much more than that.

The promos for specialist chains came to an end when Thresher’s went into administration in 2009, and Oddbins soon followed (before being rescued) in 2011. But not before they, along with supermarkets, had conditioned wine drinkers for around 15 years to believe that good wine meant discounted wine.

Where are we now?

These days, between bin ends, 3 for 2s, mix 6s, 10% for joining mailing lists... we’re still experiencing the hangover effects. It’s an arms race - nobody really wants to discount, but if one retailer does, everyone else has to follow suit.

Walking past a Nicolas shop in Notting Hill the other day, the window display was filled with discounts. If you’re living in Notting Hill, shopping in a specialist wine shop, are you really the kind of wine shopper who needs a discount?

Online it’s even worse. Up to 78% of Majestic ads in the Meta ads library for the past two years were price and offer led.

A recent promotion from Laithwaites

The worst part is that this is the first thing the customer sees in an interaction with the business.

Yes, they’re being used to entice new customers in. But ‘anchoring’ and ‘priming’ bias are coming together and conditioning customers in a way that’s harming business in the long term.

Before a customer has even set foot in the shop or website, they’re being encouraged to expect price promotions, and being taught that full price = bad.

After this as the primary interaction, you’re going to struggle to make anyone feel positive about paying full price, or stretching to the upper end of their price bracket.

Discounting and ales are part of retail. But they should be the exception not the rule. A marketing industry rule of thumb is that you should spend 60% of your efforts on brand, and 40% on sales activation. It feels like wine is hurtling towards 99% sales activation.

Two more examples of how wine clubs and online wine retailers try and sign up new members - using offers rather than the quality of what they are selling as the draw

Thankfully, the specialist chains disappearing left an opening for independents. While many do a fantastic job of avoiding discounts altogether, you don’t have to walk down too many high streets to realise how common it still is.

Wine is one of the more premium products that people buy regularly. Forty years on from the start of the wine buzz, it still has a premium aura to most people, yet it’s often sold like a roll of carpet or a second hand car.

A sale in your favourite clothes shop is great. But if it’s happening across every product, every day then you’re TK Maxx. Which is fine if you want to be a TK Maxx, but the point of difference for a specialist retailer of a premium product should be quality - not discounts.

You wouldn’t catch your high end butcher plastering BOGOF or 50% off banners off over their sausages, and if you did... would you really want to buy them?

* Tom Planer is founder of Corkable a new online wine player that looks to find the right wines for its customers in the same way that Spotify helps find you the sort of music you want to listen to. Click here to find out more.