Oak ageing, time on the lees, sparkling – just some of the ways in which Albariño producers are diversifying in Rias Baixas, particularly in years when there is a bumper harvest.

Rias Baixas, the North West corner of Spain, famous for producing Albariño, is a region that is undergoing a series of fundamental changes. Backed by a financially supportive government, with increased investment in technology and new facilities, and with interesting experiments in aged, oaked and sparkling Albariño, new ways of marketing the wine – aimed at a female-skewed demographic for example – and also wineries testing other varietals, Rias Baixas is an area that is vibrant, healthy and ready to start building on the phenomenal success it has had in the past 20 years.

For lovers of Albariño that can only be a good thing. For here is a region that feels vibrant, invigorated and confident in the product it is producing.

Over the past 20 years popularity of this racy, white wine has ramped up immeasurably, securing itself as a staple on most restaurants’ wine lists. In fact it’s now more a case of wine buyers choosing two Albariños to put on a list to give a point of difference, in much the same way that is happening with Prosecco.

Quinta Couselo in the Rosal region has managed to build a new winery with government assistance

There is even a case to be put that if you are serving molecular cuisine then a bottled of aged Albariño serves well throughout the meal as some cutting edge restaurants are doing in Barcelona and Madrid – the wine changes dramatically as it comes up to room temperature and its complexity can serve all courses.

But the basic picture is that Albariño is in boom time.

In 27 years wineries in Rias Baixas have jumped from 30 to 181 last year with sales more or less quadrupling to 21 million litres. The export picture is even more impressive having grown eight to nine fold to 5.7 million litres being exported, or 27% of regional output. Of that the UK is now the second largest market, behind the US, with 17% of the export market.

Hundreds of small vineyards near marine estuaries – a typical scene in Rias Baixas

There is a lot that is fascinating about the region

For a start there are few if any other wine regions in the world that grow just one grape and are synonymous with that one wine as in the case of Rias Baixas.

The reason is that it is the best place on Earth to grow the Albariño grape – Rias Baixas means ‘lower estuaries’ and this serated coastline of inlets and fingers of land gives the perfect climactic conditions for the grape to grow; this, combined with the grantic soil that gives the wine structure and minerality.

The coast is also perfect for rich and abundant marine life, and it has to be said that it is no coincidence that Albariño and fresh fish and seafood pair so well together, one reason that Japan is rising in the pecking order of export markets.

The actual vines are unique too.

Because of the humidity and the high levels of precipitation, vines are grown on pergolas to allow the breeze to circulate underneath – cooling and drying the grapes. In previous centuries this allowed other crops to be grown underneath, especially ones that don’t favour much direct sunlight.

As with almost everything in this neck of the woods, the pergolas all have pillars that are made out of granite. In fact, if granite is your thing, then Rias Baixas is definitely for you!

Pergolas at harvest time

The supply chain is also very different

Because of divisive inheritance laws, plots of land are tiny and hard to come by. Most wineries either do not have their own vineyards or rely on hundreds of smallholders to supply grapes – often as much as 50% of their grapes are supplied this way. One side effect of the size of the plots is that there is no mechanised picking in the region – everything has to be done by hand.

Harvest time here is signalled by lots of cars on the road towing trailers with maybe 20 or so boxes of grapes on the back – the farmers then having the grapes tested for quality, alcohol and adherence to growing regulations when they get to the winery. It’s a logistical nightmare. And quite unique.

One farmer I saw arrive with his grandson punched the air when he was told of the alcohol level of his grapes. I calculated that the 18 boxes he unloaded would be worth about €160 – for an annual harvest!

Climate change is having an impact as in other parts of the world. 2016 is a drought year with many wineries reporting a substantial reduction in yield (by as much as 20%). Last year substantial rains just prior to harvest spoiled wine in some regions. Incidentally, many of these wines tasted six months since the annual trade tasting were showing much better after more time in the bottle.

Experimenting with the wine and perceptions of Albariño

When conditions are perfect, as they were in 2011 and yields are up substantially, wineries are experimenting more with ageing in the barrel and in the bottle.

Opinion is divided on the use of oak. Some winemakers point to the traditional vinification vessels and argue that the region has always used oak, while others argue that the clarity and vivacity of the wine is not improved with the extra texture and flavours that oak brings. Almost all the wineries I visited had at least one experimental foudres on the go, if they weren’t already in reasonably large scale production of oak-aged wine as a new line.

Vicky Mareque at Pazo Senorans, one of the leading exponents of ageing Albariño

The ageing that clearly was working very well was when the wine had spent both time on the lees and time in the bottle.

One quick takeaway of the trip was that Albariño ages very well indeed.

In the case of Pazo Senorans, their aged Albariño is the regular vintage just kept back in the bottle and then labelled some three years later. Their wines were akin to aged GG dry German Riesling – keeping their precise linearity but adding layers of aged fruit and complexity.

Also a revelation was Albariño that had spent three years on the lees and then three years in the bottle. My favourite exponent of this was Adega Eidos and their Contraaparede wine that had much greater volume through the lees contact and had now become a luscious, voluptuous wine that was comparable to a 20 year-old Savenierres, or other aged chenin blanc.

Although some wineries were doing a sparkling, I cannot see this making much of a dent in Cava’s domination of the category in the domestic market. Mar de Frades’ sparkling stood out well in a range tasting and is a great aperitif served with flash-fried pardon peppers, prawns and salted almonds.

Other changes in the region are focusing on changing the perception of Albariño and not just the wine itself.

Developments here include new ways of marketing the wine, introducing new lines that appeal to both an export market and to a particular target demographic – Vionta’s You&Me, for example, is clearly aimed at a younger market, women and, with an English name, the top two export markets – the US and UK.

More niche but perhaps more interesting is the move into making wine out of grapes other than Albariño.

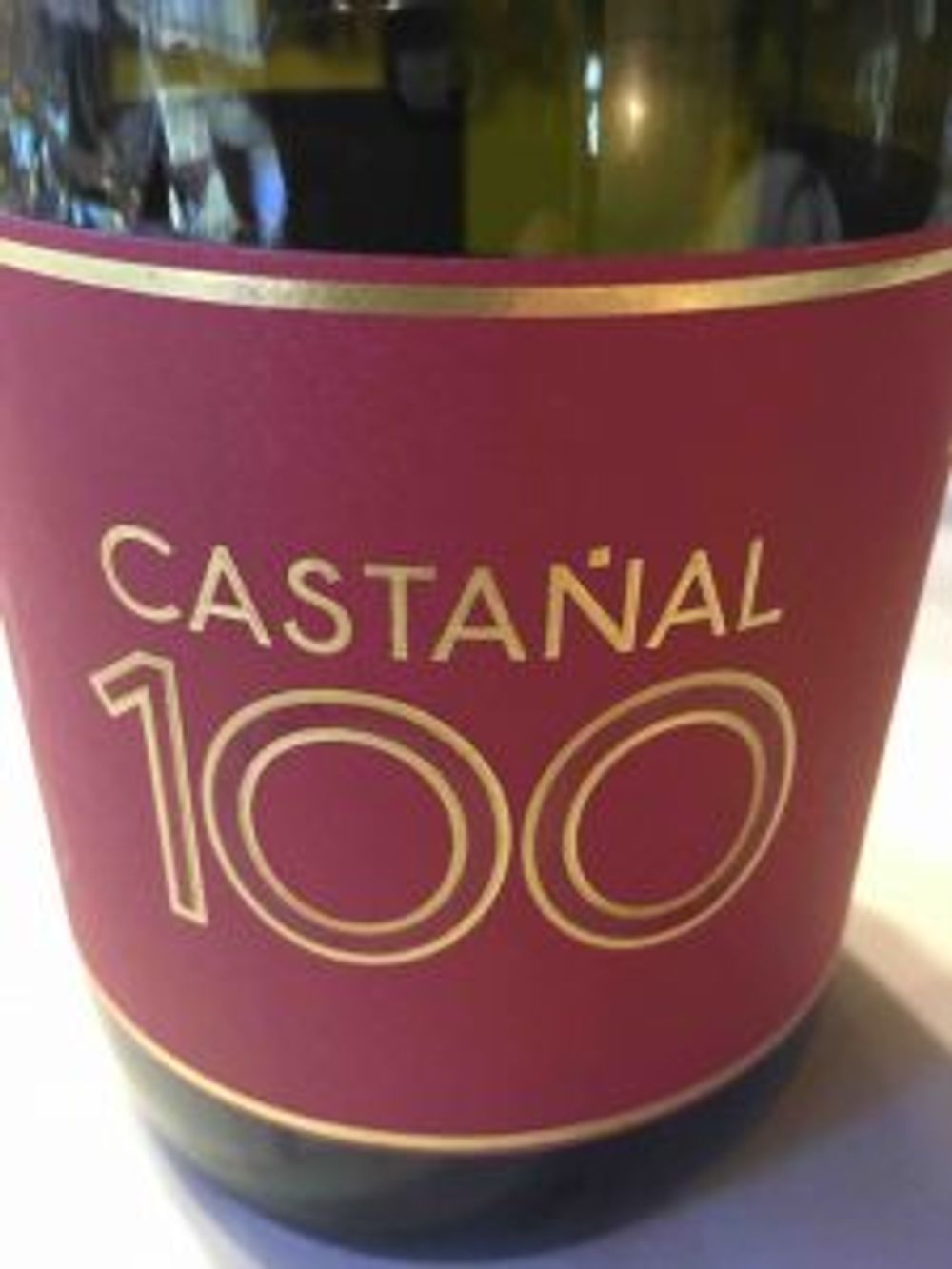

Adegas Valmiñor is a winery that has just added Castanal to its range of varietals.

Not heard of it? Not surprised.

The world’s first and only wine made from 100% Castanal

This is a wine made from an almost extinct grape that was discovered by talking to some local farmers. Castanal-100 is the world’s first 100% varietal expression of this grape and fascinating drinking it was – very taut and angular and suited very much to drinkers who like unusual, challenging wines. The wine joins the winery’s extensive range that includes a Godello and 100% Loureiro, called L-100.

Having tried over Albariños of all shapes and sizes, the trip drilled home that even in the least impressive hands the wine offers serious bang for your buck. In the entire trip I didn’t taste one wine that I thought was less than drinkable which really is high praise indeed.

Now, all the the Rias Baixas marketing bods in the DO have to do is find a way that they can get people in international markets to recognise Rias Baixas as easily as they recognise the name Albariño… and maybe even how they pronounce it!

Then they will be doing a very good job indeed.

The trip started at Rias Baixas DO for a tasting of 30 wines, these are the Albariños that The Buyer picked out as the best of the bunch, with the Pazo Senorans 2008 the very best.