“What happened to Australian wine? it used to be everywhere but now you struggle to find any on the shelf,” wondered a wine loving friend as we opened my bottle of Mornington Peninsula Pinot Noir to accompany our roast duck dinner.

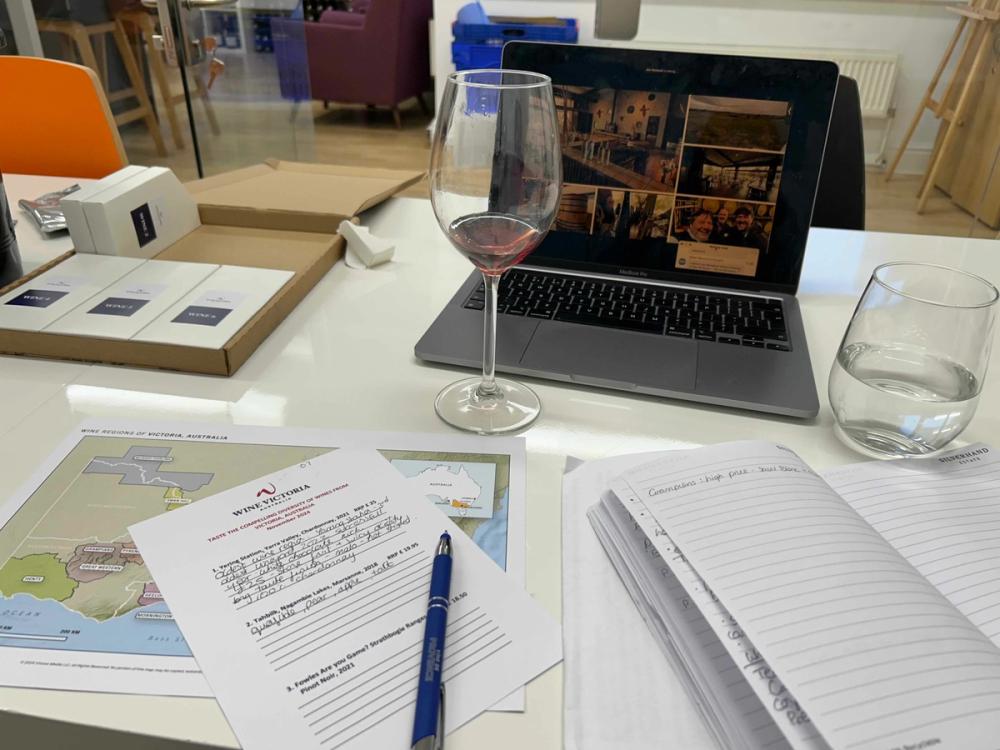

The sentiment was echoed by Joe Wadsack this month as he started a Zoom tasting of wines from Victoria, Australia’s smallest mainland state, but also probably its most geographically diverse.

“Australian wine is much less talked about today than in the late 1980s and 1990s when drinking it was seen as cool, at a time wine was taking over from beer as the main drink consumed at home,” he said.

Indeed, brands such as Jacob’s Creek, Rosemount and Lindemans were hard to escape, advertised everywhere and offering value and consistency through single varietal wines that were easy to understand and hard not to like. The UK, with its close historical ties to Australia, was the natural main export market and we drank oaky Chardonnay, full-on Shiraz and hefty Cabernet Sauvignon by the bucket load.

What happened? Changing tastes is part of the story, with the likes of Chile offering cheaper brands, but also consumers – who tend to travel more these days – wanting to experiment with different countries and styles. And for winemakers the lure of the huge Chinese market – which seemed to have an almost insatiable appetite for Australian wine, especially the heavy reds Aussie producers can make so well and the Chinese love – was hard to resist.

But “seemed” was the operative word; tariffs imposed by Beijing in 2018 killed much of the market, especially after being raised again – to 218% – in 2021 after Canberra called for an international inquiry into the origins of Covid. So producers, also faced with massive overproduction after 2021’s bumper harvest, have had to look anew at their original main export market, hoping to attract consumers with a much more diverse and generally higher quality offering than back in the 1990s.

Joe Wadsack tasting in Victoria for the Wine Victoria media events

“Australia is definitely back” said Wadsack as he introduced six very different wines from Victoria, which he travelled around on an extensive trip organised by Wine Victoria back in June.

The state is actually a great place to demonstrate Australia’s return to oenological form. Currently home to some 860 wineries spread across 21 regions, it literally produces everything, wine-wise, in part because of the geographic diversity but also a wide variety of soils and micro-climates, and ambitious producers increasingly attuned to what works in today’s complex and competitive market.

The regions are diverse, from Murray-Darling where much of the state’s bulk wine used to be made but where vines planted back in the 1970s and 1980s are now producing more interesting wines; to Henty, also bordering South Australia, home to Seppelt which dates back to 1851 and where world class Riesling is being produced; and to the Grampians, where cool climate wines are being produced in high altitude soils.

Producers include long-established names like Yering Station which was the state’s first vineyard planted in 1838, the year after Queen Victoria ascended the throne, Tahbilk which has 160-year-old vines and Mount Langi whose vines date back to the early to mid-nineteenth century.

New wave of innovation

Recent years, however, have seen the emergence of younger, more ambitious producers in regions such as King Valley, where non-French varieties have been successfully planted by growers of Italian and Greek descent (with over 400,000 Greek speakers Melbourne has the largest Greek community outside Greece).

‘Alternative varieties’ like Aglianico, Sangiovese and Barbera are increasingly proving to be more resilient than some of the classic French varieties to the effects of climate change which is a major issue here.

For an example of this new innovation, Wadsack picked Stanton & Killeen in Rutherglen, a region best known for its aged dark Muscat of which one delicious example, the Grand Muscat NV was shown here. Recognising the limitations of relying on the pricey but sumptuously sweet wines for which they are known, the owners planted Portuguese varieties Alvarinho and Arinto to make impressive, new style fresh wines.

Victoria’s best-known regions Yarra Valley and Mornington Peninsula, with iconic producers like Paringa and 10 Minutes by Tractor have by contrast focused on what they do best, making high quality Chardonnay - in a range of styles - and Pinot Noir often to world class standards. Their proximity to Melbourne has made them magnets for wine tourism, always good for the bottom line in these uncertain times.

“Why would you mess with what works so well? In the past ten years producers across all the regions have really got their act together,” Wadsack says.

So how were the wines?

Wadsack calls Australia a one-stop-shop for every kind of Chardonnay – from the fat, oaky 1990s styles to the mean and lean ones that started emerging as an over-reaction in the early 2000s.

The first wine in the tasting, Yering Station, Yarra Valley, Chardonnay 2021 falls pretty squarely in the middle of those two stylistic parameters, maybe leaning a bit on the lean side if that makes any sense. It’s a good all-rounder from Yarra Valley that works well, with floral notes and some vanilla showing in a fresh and well balanced wine. RRP £25.

Wadsack says it is something of a mystery why so much Marsanne is planted in the Nagambie Lakes region but we should be thankful when it works so well, as in Tahbilk, Nagambie Lakes, Marsanne 2018, wine number two. This is a warm region with average temperatures of 21.2°C against just 19°C a few years ago but the Rhône variety seems happy, showing roundness and good structure, its freshness enhanced by stainless steel maturing and six years in bottle, and just 12% alcohol. Good value at £19.95.

Wadsack described the Fowles Are you Game? Strathbogie Ranges, Pinot Noir 2021 as a premium wine at an entry level price (£18.50, which sort of is entry level for decent Pinot) and I would agree: this has soft grippy tannins but also some spice and dark fruit, probably courtesy of the 3% Mataro (Mourvèdre) added in what is an unusual but actually rather effective coupling. RRP £18.50.

As for the Stanton & Killeen Rutherglen, Grand Muscat NV this is a classic example of the sweet wines for which the Rutherglen has become famous. Dark brown, almost molasses coloured, there’s an intense concentration of flavour here, and an almost primal viscosity to the long finish. The wine takes some 15-20 years to get to this state, achieved mainly through evaporation. “If you think of the time, and the volume of grapes and labour here, £40 for a half bottle is actually quite a fair price” says Wadsack.

And lastly two very different versions of the same red variety, for which Australia is probably best known.

The Mount Langi Ghiran Cliff Edge Shiraz 2018 from the Grampians is, as Wadsack says, a wine that’s all about the fruit and this is supple and poised, reflecting the 30% that is aged for 14 months in new oak.

“There’s spice and cordite here, but also freshness. This is deft on its feet,” he concluded. With just 13.5% alcohol and medium-ish weight, this isn’t an old style Barossa-style head banger and all the better for it. RRP £23.50.

By contrast the most expensive wine shown (£65 RRP) is a very different beast. The Castagna Genesis Syrah 2018 from Beechworth - home also to an old gold mining town of the same name in Victoria’s north-east towards the New South Wales border- is a single vineyard stunner, and the favourite wine of the tasting. Very Rhône-like, the palate is intense, savoury but “fine boned” as Wadsack put it. Made in tiny volumes, this is a pure demonstration - like all the other wines here - of what Victoria today is capable of. Australia is back, with the Victorians leading the way.

* You can read the first part of Joe Wadsack's report on Victoria wine here.

* You can find out more about the region at Wine Victoria website here.