“These are tiny volume wines but amazingly characterful, a riposte to those who suggest Chilean wine is predictable,” writes Keay about some of the wines on show at Wines of Chile.

Alistair Cooper MW masterclass was a real eye-opener, Wines of Chile, London, September 13, 2023

This year looks set to go down as one of the worst on record in terms of natural disasters with the wine industry across Europe badly impacted, as the reality of climate change became apparent just about everywhere.

Chile has also seen its share of calamity with wildfires in February – after days of 40°C+ temperatures- ripping through several historic southern wine regions. These were followed by devastating floods six months later with the equivalent of Santiago’s entire annual rainfall devastating vineyards in Colchagua, Maule and Itata in a matter of hours. Producers have at least been spared the biblical plague of locusts and the death of the First Born but it was hard to escape a widespread sense of resignation at this year’s annual Wines of Chile tasting, held in early September at London’s Royal Horticultural Hall.

“Things have been tough, there’s no escaping that. The important thing for us now is that we hang onto and build up our market share, which isn’t easy in the current environment, which is more competitive than ever,” one winemaker told me, asking not to be named.

Helped by massive investment and modernisation over the past decade, the long thin country has become one of the world’s biggest wine exporters, last year in fourth place volume-wise after Italy, Spain and France according to the French-based International Organisation for Vine and Wine (OIV).

However, things are becoming challenging; quirky weather has impacted the 2023 harvest whilst exports for the first six months were well down, those to the UK by almost 60%. Although there are many explanations – including a shift to UK bottling for entry level wines – changing tastes is clearly at least part of it. Some 100 varieties are grown in Chile but 30% of vines are Cabernet Sauvignon, a variety that’s becoming less fashionable amongst mainstream drinkers, whilst the hefty Bordeaux blends that also make up a big chunk of Chile’s red offering are less preferred these days to lighter, fruitier wines. And especially in the on-trade… anecdotal evidence suggests an over-familiarity with the big names that dominate and have always defined Chilean wine – the likes of Concha y Toro (including Cono Sur and other brands), Santa Rita, Underraga, Errazuriz, VSPT and Montes.

A new focus on regionality

Mid-range producers have become more competitive and dynamic

Yet there is a lot more going on in Chile’s wine industry than immediately meets the eye, as this tasting to some extent made clear – although it would have been nice to see more high-end iterations of Pais, the closest Chile comes to an indigenous red variety and more white varieties rather than the clearly dominant Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay.

“Up and down the country, the rise of small producers – many of them in or near coastal regions where some great whites are now being made – has been really interesting. And mid-range producers (the £10-25 bracket) have become more competitive and dynamic,” says Alistair Cooper MW, presenting seven wines from seven varieties and seven regions in an extensive Masterclass.

Cooper, who has just released a book on the Wines of Chile, says the country is also witnessing a new focus on regionality whilst producers generally are less heavy handed, eschewing excessive use of oak and letting the vineyard and variety, rather than the winemaker, speak.

“There is a welcome trend towards doing less, to being more hands off,” he says.

This was well illustrated in the first four wines of his tasting, showing from Leyda, a very fresh, herbal but not green Sauvignon Blanc, VSPT 1865 Selected Vineyards Sauvignon Blanc 2022 (importer, John Hearn); from Traiguen-Malleco the moreish Morande Black Series Chardonnay 2021, made from grapes grown in volcanic soils in a cool region (Berkmann Wine) and from Coelemu-Itata, the fascinating MontGras Handcrafted Rare Cinsault 2022, just 12% but packed with character and nuance (North-South Wines).

Cooper maintains that another variety that has seen great strides in Chile is Pinot Noir, which I always found didn’t work and was often either too green or over-extracted – he proved me wrong by showing me the elegant, well-balanced yet forceful Errazuriz Las Pizarras PN 2021 from Aconcagua Costa (Hatch Mansfield), although admittedly at over £74 a bottle retail, this was one of the more expensive wines of the tasting.

Caring for the environment and the long term financial health of the business: Viña Ventisquero winemaker Alejandro Galaz

Testing the limits of viticulture

One producer testing the limits of viticulture in this geographically diverse country is Viña Ventisquero, a medium sized producer by Chilean standards, making around 20m bottles. The high end of its range (accounting for around 600,000 bottles) was mainly on show here and I was really taken by the Tara range. Tiny volumes and made from grapes grown in the unforgiving Atacama Desert – reportedly the driest place on earth where winemaking is also complicated by the incredibly salty limestone soil – these are as far from the mainstream as it’s possible to get. And in a good way. The range now extends to seven with two new reds, a delicious Grenache 2021 (fruit forward, ready for drinking, 1) and a Cabernet Franc 2021 (delicious but needing more time to evolve) added to the range, which includes a Chardonnay, a Sauvignon Blanc, a Pinot Noir and a Syrah. Volume remains low – just 60,000 in total – and the wines are made without intervention.

“I wouldn’t want to call these natural wines but they are sustainable, which in a way explains everything we do, covering social responsibility to those we employ, care for the environment and the long term financial health of the business,” says winemaker Alejandro Galaz.

Viña Ventisquero is also responsible for what was in my view the best Carménère of the tasting. Quite a few of the wines at the self-pour ‘Karma Carménère’ table showed how diverse this wine can be depending on winemaker and, increasingly, on region; I loved the Chateau Los Boldos Gran Reserva Carménère 2022 – very fruit-driven, dark with red berry fruit – from Cachapoal Andes and the very different Carmen Gran Reserva Carménère 2022 from Colchagua, elegant and layered with a distinct cigar box character. But Viña Ventisquero’s award-winning Obliqua 2021 (94% Carménère, 4% Cabernet Sauvignon, 2% Petit Verdot) from the highest vineyard in Apalta blew me away, full on, chocolate and coffee, some tobacco but lots of jammy character.

“We’ve worked hard on this wine, with softer extraction but a desire to show the regional character, and the grape, which should always be generous,” says Galaz.

Close by, Valdivieso – probably best known in Chile for its sparkling wine – was showing its intriguing Caballo Loco range, five grand crus made from five different regions; the Caballo Loco Grand Cru Apalta 2021 (85% Carménère, 15% Cabernet) is truly outstanding, a full, rich, moreish palate showing forest fruit and plum, with great length and elegance, whilst the multi-blend Caballo Loco NV 20 NV – a blend of the five grand crus comprising some 10 varieties, led by 50% Cabernet Sauvignon – is even more intense, showing dark berry fruit and enormous character. Valdivieso was also previewing its Caballo Blanco, another fascinating blend this time of 45% Chardonnay, with the remainder comprising Pinot Noir, Moscatel de Alexandra, Viognier, Semillon and a few other varieties. These are tiny volume wines but amazingly characterful, a riposte to those who suggest Chilean wine is predictable.

VSPT’s John Hearn: trying to give Prosecco a run for its money.

John Hearn of the VSPT wine group is taking this approach to heart by importing three new tank-fermented sparkling NV wines to the off-trade, Ritmo Extra Brut, Ritmo Brut and Ritmo Rosé, all made from 100% Moscatel with 10% alcohol. He says a deal with a UK supermarket group is imminent and reckons the wines – very light and fresh, and with an alcohol level which takes advantage of the government’s new tax system, will do very well.

“Chile hasn’t been well represented over here in the sparkling wine sector and these wines, made from a crowd pleasing, easily accessible variety, make a great alternative to Prosecco, and at a great price,” Hearn says.

And finally, two great wines from two of the best known producers in Chile.

From Concha y Toro, the delicious Amelia Chardonnay 2021: rich, barrel-fermented in old French oak, this has amazing depth but also great freshness reflecting the fact the grapes come from Quebrada Seca in the Limari Valley (previously the grapes came from much warmer Casablanca).

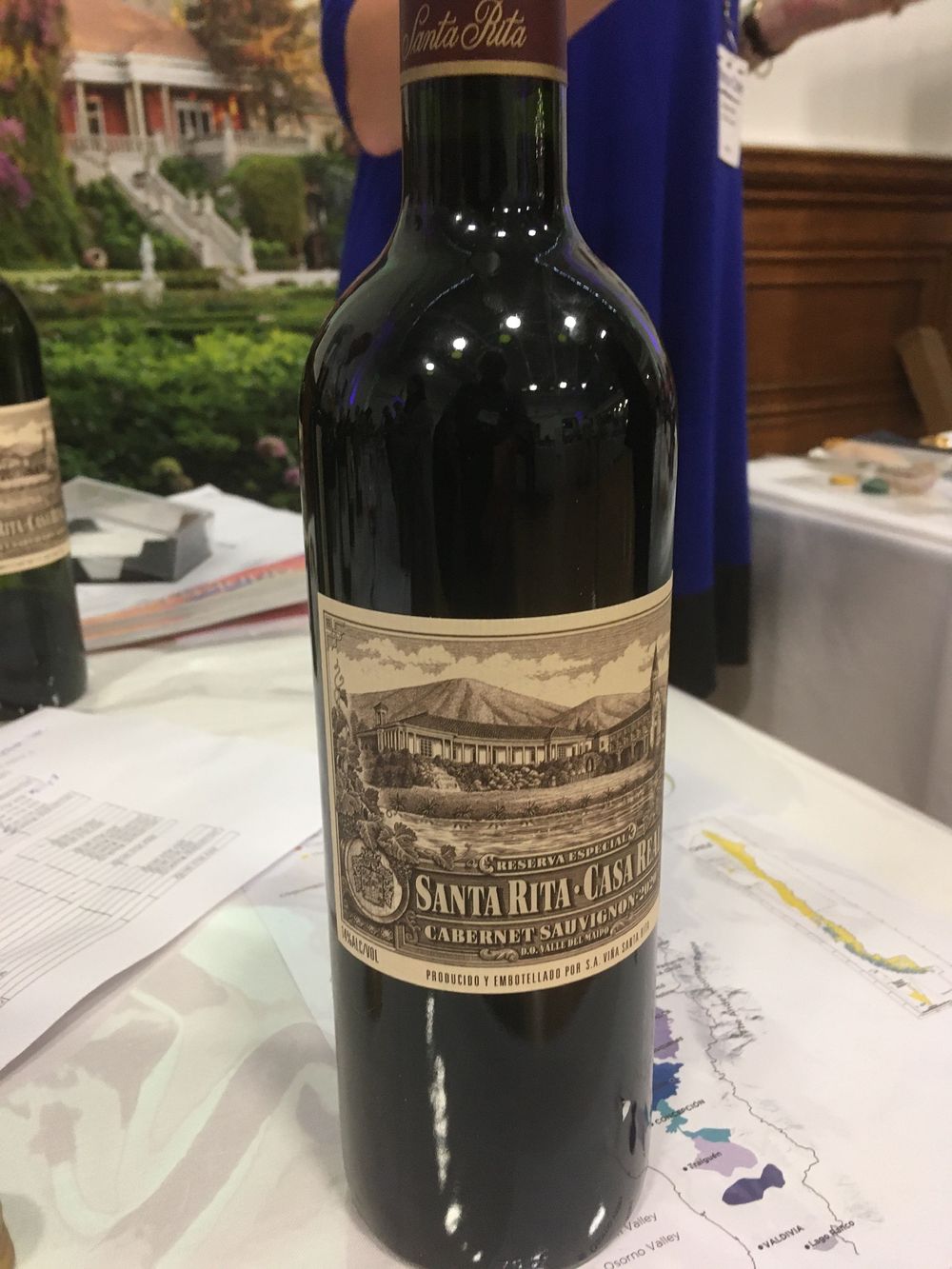

And finally, although my intention was not to focus on Cabernet Sauvignon I couldn’t resist a mention for one of Chile’s icons, Santa Rita’s Casa Real Reserva Especial Cabernet Sauvignon. The 2020 vintage is deliciously moreish, showing dark and red berry fruit made from grapes grown in Buin in the Maipo Valley.

So what was my take-away from this tasting? Chile’s wine scene is clearly evolving, focusing more on regionality, freshness and tilting slightly away from the old dependence on Bordeaux varieties; however it can still do what it was always famous for, very well indeed, and especially so at the high end. Perhaps even more than in recent years, this is a country to follow closely.